The Sandwich That's Eating Charlotte

Báhn Mì shops are popping up all over Charlotte — and not just in traditional Vietnamese neighbothoods. There's a very good reason for that.

Bánh Mì sandwich shops might not ever match the presence of Bojangles in Charlotte, but it’s getting easier to find the classic Vietnamese sandwich throughout the Queen City.

Charlotte’s iconic Le’s (pronunced “Lay’s”) Sandwiches & Cafe is recognized as having opened Charlotte’s first bánh mì shop in 2004, inside the Asian Corner Mall. Since then, Vietnamese restaurants in Charlotte have offered the sandwich. (And in happy news for bánh mì fans, as first reported by Unpretentious Palate and then CharlotteFive, Le’s will be staying in the family. Owners Minh Quang Nguyen and Le Thi Le-Nguyen were looking to sell the business to make way for retirement, but son Tuan and his wife Emily have agreed to keep the business in the family.) They have a lot more company now.

One reason for this, of course, is that the Vietnamese population in Charlotte continues to grow. But there’s another reason: The bánh mì is an amazing, flavor-packed sandwich, unlike anything else. The result of French colonialism, two world wars, and Vietnam’s fight for independence, the bánh mì is — along with Phở — Vietnam’s most popular culinary export.

For the record, bánh mì actually refers to ‘bread’, or ‘wheat cake.’ The original pork, pâté, and pickles sandwich is known as a bánh mì thịt ngoui, ‘bread, meat and cold cuts.’ Or as it’s also sometimes known, bánh mì đặc biệt, — ‘the special.’ The most popular bánh mì at most local shops is usually the lemongrass-marinated grilled pork version. It's not the original — if anything, it's even more Vietnamese.

Hao Doan

Bánh Mì Brothers

Hao Doan and his older brother Luan opened Bánh Mì Brothers in the university area in 2016. The brothers grew up in Virginia Beach, where their parents settled after fleeing the communist regime in Vietnam.

“Like many others, our parents escaped by boat. After a year and a half in a refugee camp in Malaysia, we came to the States in 1980.” At the Doan household, a roll of paper towels and a 2-liter Coke each had to last a month. “The Coke would be flat,” says Hao. “But we would drink it. My mom was great at stretching everything out like that.” And while other children’s parents showed up at school functions, Hao notes that at his soccer games, for example, his parents were absent, “because they were always working.” Hao and Luan’s mother worked as a waitress and as a janitor, and their father always had two jobs.

“Like many others, our parents escaped by boat. After a year and a half in a refugee camp in Malaysia, we came to the States in 1980.” At the Doan household, a roll of paper towels and a 2-liter Coke each had to last a month. “The Coke would be flat,” says Hao. “But we would drink it. My mom was great at stretching everything out like that.” And while other children’s parents showed up at school functions, Hao notes that at his soccer games, for example, his parents were absent, “because they were always working.” Hao and Luan’s mother worked as a waitress and as a janitor, and their father always had two jobs.

“Our parents did a great job raising us, busting their butts to give us a comfortable life. We knew we were poor, but my parents always provided,” says Hao. “We played tennis, and we rode our bikes for hours. It was a typical life. But they weren’t getting anywhere. And then the Naval base closed down, which had a really bad effect on the local economy.”

Hao’s aunt (on his mother’s side) had moved to Charlotte. She and Hao’s mother decided to open a nail salon on East Boulevard.

Luan always enjoyed American fare, but Hao preferred his mother's traditional Vietnamese cooking. While attending Virginia Tech to study finance (which his brother also studied), he missed it.

“So I started cooking for my friends at school. I would call home and ask my mother for her recipes. She would always say, ‘Hao, you have a meal plan. I want you to study.’ ”

Hao studied — and continued to cook —and after graduating, he enjoyed an 18-year career with The Vanguard Group, an investment advisor company.

“I enjoyed working at Vanguard, but in 2016, I decided to take a leap of faith and open the restaurant.” Not surprisingly, Hao’s mother wondered why he would want to sacrifice a secure job and its 401k for the vagaries of the restaurant business. “When we first opened — before we got our processes in place, I might be here until 2 a.m. prepping food,” relates Hao. “Mom would say, ‘Are you happy now? You could be in bed sleeping!’ But in fact, I was happy. I just love cooking.” Luan is a full partner but continues to work in finance.

The Doan brothers’s original plan was to open a full-scale Vietnamese restaurant, but the expense was too high. Hao is friends with the owner of Crispy Bánh Mì, which opened in June 2016 and now has three locations in Charlotte. “He was doing really well with bánh mì, and he helped me open Bánh Mì Brothers.” The restaurant got off to a great start, and then in its third year, the pandemic hit.

“It didn’t really hit me at first. Things slowed down, but then on that Friday when everything had to shut down, we did about $400 in sales that day. And we were stuck doing $400 in sales a day. So we had to readjust.”

“We did carryout, and fortunately, bánh mì is a great carry-out item. Customers would call and pay over the phone, come to the door, and we would hand them their order,” says Hao. “That helped protect our staff and our customers. Then, because we only had the one phone line, people would call and get a busy signal. So we went to online ordering and got an app to handle that. And actually, within two to three months, our sales were almost back to normal.”

The federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) helped cover salaries for the staff, and Hao also credits his landlord, who was willing to provide a few months of free rent, while extending the lease with no increase for the next five years.

“We did have to close down for a week. We hire a lot of students from UNC Charlotte, and one one employee got COVID,” says Hao. “We shut down and cleaned everything. It was a lot of additional stress — who can work this day? who has been exposed to COVID and has to stay home? We re-opened May 4 last year, and like everyone else, added the plastic shields. Now we are doing better than ever.”

Bánh Mì Brothers’ customer base is clear evidence of the sandwich’s universal appeal. “It’s true. Our customers come from all walks of life. Wells Fargo is down the street, there’s an office park, the university, of course, and we are right across the street from Atrium Health University City hospital.”

The restaurant gets students coming in for coffee before classes, and with all the offices nearby, it does a big lunch rush. One customer segment that might surprise some people is vegans.

“I would say that abut 45% of our customers are vegan. I am so grateful for them, and I have learned a lot about the differences between vegans and vegetarians,” says Hao. He initially served one vegan bánh mì, but was still using regular mayonnaise. “Customers would ask, ‘Why not use vegan mayonnaise?’, so we started making our own vegan mayonnaise. Now we have four vegan sandwiches on the menu.” Hao says he isn’t going to get too crazy with the bánh mì variations.

“I am not going to stray too far from the traditional bánh mì. I do love creating in the kitchen, though, so to keep things fresh, we do a special bánh mì of the month. It’s not on the regular menu, but we’ll feature something different, like soft shell crab bánh mì, spare rib bánh mì — and I am thinking of doing a duck breast bánh mì.”

Hao’s parents now live about a block away from the restaurant and come by the shop regularly. “When we first opened, they would come in and ask, ‘How is business, is it slow?’ That was stressful. It’s not so much any more — although maybe a little — but they are more relaxed, and I give them the sales figures each day. It’s been a good move. I didn’t realize until a friend told me that we are value to our parents. We are valuable to them. And parents never stop being parents. So that helped me see the other side of it. To this day, they want what they think is best for me. And I better appreciate that now. This was a good move and still is. I’m enjoying life. I work from 12 to 7. It’s comfortable. I am appreciating life.”

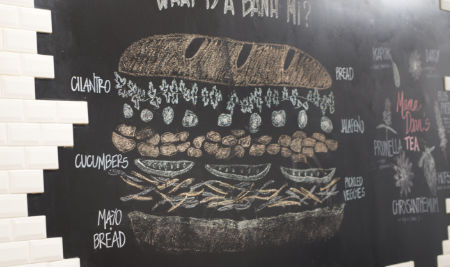

Now, about those ingredients...

Is there rice flour in that baguette? Maybe. With the First World War causing supply disruptions to French Indochina, rice flour was approved to make the bread. Once the war ended, the French went back to using wheat flour, though rice flour continued to be used in small quantities, to combat the humidity. The bread's characteristic fluffiness comes from dough enhancers, such as ascorbic acid, premixed additives, or sometimes chicken or even duck eggs.

What's with the cold cuts? The original bánh mì was derived from the traditional French plate of ham, cold cuts, and pâté, served with cheese, a baguette, and butter. The Vietnamese were not allowed to or couldn't afford to eat the food imported by the French colonialists. (Nor did the French eat any of the local cuisine.) At the outbreak of World War I, a large supply of French items became available to the Vietnamese. The two main importers of French food products were German companies, and as thousands of French officials and soldiers stationed in Indochina set off to France to assist with the war effort, the Vietnamese market was suddenly flooded with a surplus of European products, all at discounted prices.

Mayo? Mine had butter... During World War II, anti-French sentiment increased, and butter was replaced with mayonnaise, a cheaper ingredient that was also more stable in Vietnam’s heat. But butter still works, and may be a better option in certain versions of the sandwich.

Who added the pickled vegetables, cilantro, and jalapeno? Once the bánh mì began to gain a following in Saigon, with a shop called Hoà Mã at the center of it all, vendors all over Saigon began copying, borrowing, stealing, and improving on each other’s recipes. Read the brief history below for more details.

Anything else? Of course. As a finishing touch, you might be inclined to add a few splashes of Maggi Seasoning, a Swiss product that's been owned by Nestle since 1947 and is ubiquitous throughout Asia (and elsewhere). Or squeeze out a squiggle of Vietnamese red chili sauce.

A Brief History of Bánh Mì

The bánh mì as we know it didn’t exist until the late 1950s. Its story, though, begins 100 years before that, when French troops launched a 30-year conquest of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos — or what would become known as Indochina (or French Indochina). By the early 1900s, parts of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) were beginning to look like a young European city, and the French imported not just their architecture, but also their cuisine, including the ubiquitous baguette — which they ate exclusively.

The Vietnamese called the imported baguettes bánh tày, or ‘Western cake.’ The French would typically serve them on a platter with ham, cold cuts, pâté, cheese, and butter — or what is known as a casse croute (break the crust). The French did not want the local population eating their food, which they considered superior to the local fare — nor could the Vietnamese afford it. The outbreak of World War I in 1914, though, resulted in both a surplus of European food products and a reduction of the French in Vietnam. Meanwhile, about 100,000 Vietnamese men were sent to Europe to fight alongside the French. There, they got a taste of European food, not to mention an increased distate for their French masters. After the war, bread had become a common item in the Vietnamese diet.

The French, of course, stayed in Vietnam after the war, proclaiming their presence in southeast Asia as a mission civilisatrice, a political rationale for military intervention and colonization. It purported to facilitate the modernization and the Westernization of indigenous peoples. The reality, however, was profiteeering, harsh subjugation, and brutal exploitation.

Once again, a world war interceded. When Japan invaded Indochina in 1940, the Vietnamese saw an emerging Asian empire. One year later, amid increasing calls for independence, Ho Chi Minh answered with the establishment of the League for the Independence of Vietnam, the Viet Minh.

As anti-French sentiment increased, bánh tày (Western cake) became bánh mì (wheat cake), and the French casse croute platter became the Vietnamese cát-cụt. By the end of 1946, the Japanese were gone, and the Viet Minh were at war with France. Eight years later, France agreed to end hostilities, and Vietnam was sliced in two, with Ho Chi Minh’s communist government in North Vietnam, and a U.S.-backed republic in the south. An estimated one million northern Vietnamese — who became known as Bắc 54, “the Northerners of 1954” escaped to the south before the border was closed.

Among them were the Le family, who fled their village of Hoà Mã near Hanoi in the north, for Saigon in the south. Mrs. Le had worked for a French-owned company that supplied European-style hams and processed meats to French restaurants. She and her husband opened Hoà Mã’s, a cát-cụt shop at 511 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Street in Saigon’s District 3. This is where the modern bánh mì was born. (They moved a few blocks away a couple years later, and continue to this day to operate Như Lan, a restaurant, bakery, and delicatessen in Saigon.) Mrs. Le made her own processed meats, and they sold the cát-cụt platters to local students, office workers, and laborers. Mrs. Le’s husband is credited with turning the cát-cụt platter into the modern day bánh mì. He reduced the size of the baguette and replaced some of the meat with vegetables to make the platter more affordable. Observing that customers often took their platters with them, Mr. Le began stuffing the ingredients into the bread. Thus was born the bánh mì.

Among them were the Le family, who fled their village of Hoà Mã near Hanoi in the north, for Saigon in the south. Mrs. Le had worked for a French-owned company that supplied European-style hams and processed meats to French restaurants. She and her husband opened Hoà Mã’s, a cát-cụt shop at 511 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Street in Saigon’s District 3. This is where the modern bánh mì was born. (They moved a few blocks away a couple years later, and continue to this day to operate Như Lan, a restaurant, bakery, and delicatessen in Saigon.) Mrs. Le made her own processed meats, and they sold the cát-cụt platters to local students, office workers, and laborers. Mrs. Le’s husband is credited with turning the cát-cụt platter into the modern day bánh mì. He reduced the size of the baguette and replaced some of the meat with vegetables to make the platter more affordable. Observing that customers often took their platters with them, Mr. Le began stuffing the ingredients into the bread. Thus was born the bánh mì.

Other shops in the district made their own innovations, and eventually other versions emerged, including the popular bánh mì made with lemongrass-marinated grilled pork. Thus the sandwich, born out of French colonialism, has become a quintessentially Vietnamese staple and one of the country's most famous food exports.

Where to Find Báhn Mì Shops around Charlotte

You can also find bánh mì at many Vietnamese restaurants. These particular shops specialize in bánh mì.

Hao Doan's Pickled Vegetables for Bánh Mì

Ingredients

- 2 large carrots, peeled and cut into thick matchsticks

- 1 large daikon, peeled and cut into thick matchsticks

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 teaspoons plus ½ cup sugar

- 1 ¼ cups distilled white vinegar

- 1 cup lukewarm water

Instructions

- Place the carrots and daikons in a bowl and sprinkle with the salt and 2 teaspoons of the sugar. Use your hands to knead the vegetables for about 3 minutes, expelling the water from them. Then let them sit for about 30 minutes. They will soften and liquid will pool at the bottom of the bowl. The vegetables should have lost about one-fourth of their volume. Drain in a colander and rinse under cold running water, then press gently to expel extra water. Return the vegetables to the bowl if you plan to eat them soon, or transfer them to a 1-quart jar for longer storage.

- To make the brine, in a bowl, combine the ½ cup sugar, the vinegar, and the water and stir to dissolve the sugar. Pour over the vegetables. The brine should cover the vegetables. Let the vegetables marinate in the brine for at least 1 hour before eating, best if they sit overnight. They will keep in the refrigerator for up to 4 weeks.

SHARE THIS PAGE